While there are challenges to consider in a full-arch dental implant rehabilitation, it is possible to provide immediate fixed provisionals when careful technique is followed.

By Michael Tischler, DDS

When a patient presents for full-arch rehabilitation with dental implants, the clinician has different options with respect to transitioning a patient through the process. The options available to the clinician include both removable and non-removable prostheses. The authors review the options available and focus on the benefits of using a patient’s existing teeth in an interim manner for a fixed provisional prosthesis. Two case examples are presented.

The task of rehabilitating a patient’s entire arch with dental implants is challenging and is often multidisciplinary. The treatment can involve hard- and soft-tissue grafting and sometimes sequencing of dental implants for loading. The treatment sequence time can often be lengthy due to bone grafting and the amount of implant healing time needed. The literature supports immediate loading of dental implants, but there are times when implants cannot be loaded because of insufficient stability at placement or the need to graft bone before or during placement.1

The treatment sequence for full-arch rehabilitation with dental implants may vary depending on the condition in which the patient presents.2 An edentulous patient with a pre-existing denture offers fewer challenges to a clinician than a patient who has teeth and does not want to wear a denture during the treatment period.3 It is the patient who does not want to or cannot wear a denture who offers challenges and opportunities to the clinician for the transitional time during treatment.4 The reasons some patients cannot wear a partial or complete denture include gagging reflexes, occupational issues related to speech impediments from a denture, and psychological reasons for not wanting to wear a denture.

One clinical challenge inherent with provisionalization is how to avoid pressure on areas in the mouth that are being grafted for bone or where there are implants, which the clinician does not want to disturb during healing because of soft or inadequate bone.5 This is especially true when using removable dentures. The choice of how to provisionalize a patient also must take into consideration the patient’s esthetic demands and chewing capabilities as well as the phonetic aspects of the patient’s speech.6,7 The starting point in determining the best option for the patient begins with a discussion with the patient about the different options available and the pros and cons of each option.8 This is part of the informed consent process and treatment planning. Lifestyle and occupational considerations should be taken into account as part of the decision process.

There are advantages to a fixed provisional prosthesis compared to a removable prosthesis.9 A fixed prosthesis offers the patient who has never worn a denture a more natural transition during the implant rehabilitation process.10 A fixed provisional is usually less bulky than a removable appliance and creates fewer problems with phonetics than a removable full or partial denture. A fixed provisional is more stable than a removable appliance, and it allows soft tissue to be sculpted around an implant or bone graft for the emergence profile formation. One of the main advantages of a fixed provisional over a removable alternative is its ability to allow undisturbed healing of a graft site or implant site. Even when a denture is relieved, there is a greater chance of pressure on an area that a clinician is trying not to disturb.

A fixed provisional prosthesis does offer challenges and caveats. One main disadvantage of a fixed plastic provisional is the potential for breakage.11 Implant and grafting cases often require long-span areas to provisionalize. Breakage can easily occur unless these areas are supported by fiber or reinforced with metal.12 Once a fixed provisional does break, it can cause an emergency esthetic or functional problem for the patient.

Removable provisional options are less prone to breakage, and duplicates—which patients can place themselves—can be made if needed. A fixed provisional can pose hygiene challenges; this is especially true during soft-tissue healing, when changes are occurring in a rapid manner. While both removable and fixed provisionals can adequately meet a patient’s esthetic needs, a fixed provisional often becomes stained and is more difficult to clean. This is especially true when a patient is using chlorhexidine, which has a propensity for staining.13

When the patient and clinician choose a fixed provisional, careful planning is needed while transitioning a full arch for implants or grafting. The decision as to which natural teeth to use for support must be made carefully, based on the support of the provisional and how that will tie in with implant placement.

The basic concept of sequencing is to use teeth that are deemed hopeless or designated for removal to support a fixed provisional. Often an educated guess must be made about whether a tooth can support a provisional for the amount of healing time needed.

In some cases with very unstable teeth, questionable teeth are used until some implants can be loaded to provide support for a provisional. Once these implants are loaded, more implants can be placed and allowed to heal. This implant sequencing adds to the treatment time, but it allows the patient to have a fixed provisional during the entire treatment time. At times, root canal therapy needs to be performed on the teeth that will be removed to avoid pain or infection during the treatment process. There are times that certain implants are loaded as part of the sequencing process.14

A 65-year-old man with an unremarkable medical history presented with numerous maxillary teeth with questionable prognoses (Figure 1). The patient indicated he was tired of dealing with the periodontal and root canal issues he faced with his remaining teeth. He was seeking a solution that would offer him the longest-term prognosis to be able to chew and smile. The treatment options consisted of removing the questionable teeth and replacing them with either dental implants or a removable partial denture.

The patient decided that his career and lifestyle dictated that replacement of all the existing teeth with dental implants supporting a fixed implant bridge would be in his best interest. A further discussion about transitioning to the final prosthesis revealed an aversion to wearing a denture during the process.

A plan was presented to use teeth Nos. 2, 5, 9, and 14 as temporary abutments to support a provisional prosthesis. These teeth would be removed after the implants healed, and they would then be replaced with pontics and cantilevers. Dental implants would be placed in areas Nos. 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, and 13. The final prosthesis would be a cement-retained, full-arch, splinted porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) restoration.

After atraumatic removal of teeth Nos. 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14, a laboratory-processed, wire-reinforced provisional was delivered. The advantages of a laboratory-processed provisional are numerous, and include increased strength and a refined finish. A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan was performed, and the available bone, as indicated by the CBCT, showed that implant placement was possible in the planned locations with simultaneous bone grafting. After a 2-week period of time, implants were placed in the planned positions with simultaneous bone grafting using demineralized freeze-dried bone (Figure 2).

The patient then wore the provisional restoration for 3 months while the implants osseointegrated. After 3 months, the implants were uncovered, and healing caps were placed. The patient continued to wear the provisional restoration at this time. Two weeks after implant uncovering, the tissue around the implants appeared to be healthy (Figure 3). A closed-tray impression was taken of the implants, then abutments were created, as was the new provisional restoration on the new abutments. The next appointment after the impression consisted of abutment delivery, extraction, and grafting of teeth Nos. 2, 5, 9, and 14, and delivery of a new full-arch provisional restoration (Figure 4).

After a framework try-in, the final PFM full-arch splinted restoration was delivered (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

The patient retained a fixed provisional prosthesis throughout the treatment sequence. Teeth Nos. 2, 5, 9, and 14 were temporarily used to support the provisional prosthesis. Once they were removed, first an implant-supported provisional, then a permanent PFM full-arch bridge was cemented.

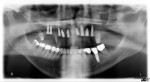

A 56-year-old man in good overall health presented with a full-arch splinted PFM bridge with abutments on teeth Nos. 4, 6, 11, 12, and 13. The previous bridge had a poor prognosis with multiple pontics and the abutments had moderate-to-advanced bone loss (Figure 7). The patient did not want to wear a full denture at any point in the future, and the authors understood that intervention at this stage could avoid that.

After a CBCT scan was taken, a treatment plan was created to make a full-arch provisional wire-reinforced restoration, which would be supported by teeth Nos. 6, 11, and 13, with implants being placed in positions Nos. 2, 3, 5, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 15. Bilateral sinus grafting was performed in the posterior maxilla, simultaneous with implant placement of Nos. 2, 3, 14, and 15. The provisional restoration had small cantilevers distally with the purpose of mainly esthetics and little chewing capability. Periodontal therapy was performed on teeth Nos. 11 and 13.

After a healing period of 6 months, implants Nos. 2, 3, 5, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 15 were uncovered and healing caps were placed (Figure 8). A new provisional was created, and Nos. 2, 3, 5, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 15 were loaded. Tooth No. 6 was extracted and an implant was placed and simultaneously loaded along with the other implants with the provisional (Figure 9).

Final impressions were taken and PFM bridges were created in three sections for the arch (Figure 10 and Figure 11). Teeth Nos. 11 and 13 were maintained, as their periodontal health was improved, offering a good long-term prognosis.

When treatment planning the replacement of teeth with dental implants in a full arch, existing teeth can be used to create a fixed provisional restoration. A fixed provisional restoration can offer certain advantages over a transitional denture. These advantages include the ability to sculpt tissue, improved speech, and improved chewing capacity. The exact sequencing to stage existing teeth to support a fixed provisional is generally different for every clinical situation. The two cases presented in this article show the variation in each clinical situation, yet how clinical success can be achieved in different ways.

1. Raes F, Cosyn J, De Bruyn H. Clinical, aesthetic, and patient-related outcome of immediately loaded single implants in the anterior maxilla: a prospective study in extraction sockets, healed ridges, and grafted sites. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2012; Jan 17. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2011.00438.x. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Jivraj S, Reshad M, Chee WW. Transitioning patients from teeth to implants utilizing fixed restorations. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2008;36(8):599-606.

3. Cordaro L, Torsello F, Ercoli C, Gallucci G. Transition from failing dentition to a fixed implant-supported restoration: a staged approach. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2007;27(5):481-487.

4. Chronopoulos V, Kourtis S, Katsikeris N, Nagy W. Tooth- and tissue-supported provisional restorations for the treatment of patients with extended edentulous spans. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2009;21(1):7-18. Erratum in: J Esthet Restor Dent. 2009;21(2):70.

5. Chaimattayompol N, Emtiaz S, Woloch MM. Transforming an existing fixed provisional prosthesis into an implant-supported fixed provisional prosthesis with the use of healing abutments. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;88(1):96-99.

6. Conte GJ, Fagan MC, Kao RT. Provisional restorations: A key determinant for implant site development. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2008;36(4):261-267.

7. McCord JF, Smith GA, Quayle AA. Aesthetic provisional restoration for the partially edentulous, immediate, postimplantation patient. Int J Prosthodont. 1992;5(2):154-157.

8. Tischler M. Treatment planning implant dentistry: An overview for the general dentist. Gen Dent. 2010;58(5):368-374.

9. Szentpétery AG, John MT, Slade GD, Setz JM. Problems reported by patients before and after prosthodontic treatment. Int J Prosthodont. 2005;18(2):124-131.

10. Drew HJ, Alnassar T, Gluck K, Rynar JE. Considerations for a staged approach in implant dentistry. Quintessence Int. 2012;43(1):29-36.

11. Fahmy NZ, Sharawi A. Effect of two methods of reinforcement on the fracture strength of interim fixed partial dentures. J Prosthodont. 2009;18(6):512-520.

12. Geerts GA, Overturf JH, Oberholzer TG. The effect of different reinforcements on the fracture toughness of materials for interim restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 2008;99(6):461-467.

13. Bagis B, Baltacioglu E, Özcan M, Ustaomer S. Evaluation of chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinse-induced staining using a digital colorimeter: An in vivo study. Quintessence Int. 2011;42(3):213-223.

14. Margossian P, Mariani P, Stephan G, et al. Immediate loading of mandibular dental implants in partially edentulous patients: a prospective randomized comparative study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 201;32(2):e51-e58.

Michael Tischler, DDS

Private Practice

Woodstock, New York

Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 4 Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 7 Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 10 Figure 11